Did the Constitution of India borrow ideas and many of its stand out features from the constitutions of other countries?

Yes, after intense scrutiny, it turns out that our founding fathers liberally chose what features to embed into our Constitution and in many cases remoulded them to suit diverse local realities.

“There is nothing to be ashamed of in borrowing. It involves no plagiarism. Nobody holds any patent rights in the fundamental ideas of a Constitution,” said Dr BR Ambedkar, the Chairman of the Drafting Committee,

So, what did our founding fathers borrow from the rest of the world?

‘The Ayes Have It’- The United Kingdom

For starters, India borrowed its parliamentary system of government from the British. What follows is the primacy of the rule of law, the legislative procedure, cabinet system, parliamentary privileges, bicameralism (Lower and Upper House of Parliament).

While the United Kingdom today allows for dual citizenship, India borrowed the idea of single citizenship from them.

Beyond ideas emerging from the British Constitution, India also borrowed heavily from the Government of India Act, 1935, passed by the British Parliament—a Constitution of India of sorts formulated by the British for India.

Among other things, the bill highlighted the role of the Governor, Judiciary, Public Service Commission and other critical administrative details like the Federal system.

These are indeed facets we borrowed, but unlike the British version of what they thought best suited India like separate electorates for minorities, the framers of the Indian Constitution did away with it.

Fundamental Rights- United States of America

When the Constituent Assembly first convened on December 9, 1946, then Interim President of the Constituent Assembly Sachchidananda Sinha urged all delegates in attendance to study the United States Constitution, drafted in 1787.

He called it “the soundest and most practical and workable republican constitution in existence.” However, he advocated no “wholesale adoption, but for judicious adoption of its provisions.”

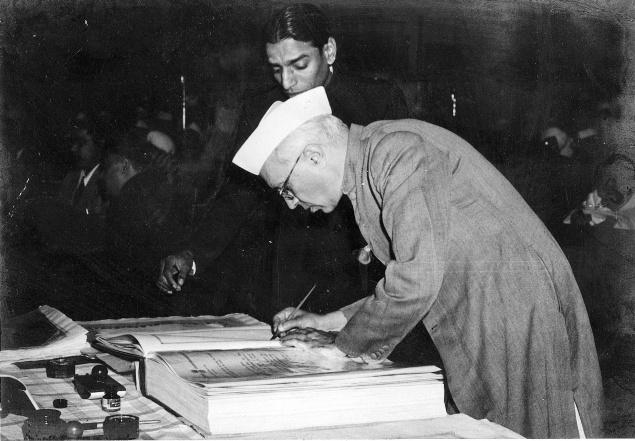

Dr Rajendra Prasad eventually replaced Sinha.

Dr BR Ambedkar was also heavily influenced by the US Constitution. Before he began work as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee, he submitted a proposal titled the United States of India, which espoused among other things, greater federalism which gave states a lot more power—a model of the US federal system of government. The very idea of Fundamental Rights was borrowed from America’s Bill of Rights.

Even our preamble, which begins with “We the people”—a phrase which confers ideas of equality—came from the US Constitution. Go further and compare the two preambles and the language used is distinctly similar. Concepts of the rule of law, independence of the judiciary, judicial review of acts by legislative bodies, and the process of impeachment came from the US Constitution.

Directive Principles of State Policy- Ireland

Irish scholar Cathal O’Normain once wrote in the 1963 Indian Yearbook of International Affairs, “perhaps the Irish Constitution’s greatest claim to future fame will depend on the extraordinary influence which its Directive Principles had on the Constitution of India.”

Article 45 of the Irish Constitutions, states: “the principles of social policy set forth in this Article are intended for the general guidance of the Oireachtas exclusively, and shall not be cognizable by any court under any of the provisions of this Constitution.”

India adopted its Directive Principles of State Policy from this provision, as Article 37 of the Indian Constitution states: “The provisions contained in this part shall not be enforced by any court, but the principles therein laid down are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country, and it shall be the duty of the state to apply these principles in making laws.”

Also Read: When Iron Man Built The Steel Frame: Why Sardar Patel Is The ‘Patron Saint’ of the IAS

Federalism- Canada

While the British and Americans influenced the principle of federalism that India adopted, it is Canada, which shares the closest link with India.

“Canada in 1867 and India in 1950 adopted a form of government broadly similar in principle to the Westminster model prevalent in England, but with the modification that they added onto a parliamentary framework a federal component. This combination of parliamentary and federal principles of government was necessitated by social and regional diversities characterising these two countries,” says this academic paper.

The similarities extend to the fact that “both are parliamentary and federal democracies, and both have institutionalised judicial review of constitutional matters.”

‘Concurrent List’-Australia

The distribution of state power in India is divided along the lines of three lists—Union List, State List and Concurrent List—as espoused in the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution. While the first two outlines the jurisdiction of the Union and State government power respectively, the Concurrent list includes subjects that give powers to both the Centre and State governments like education, family planning, population control, protection of wildlife, etc.

This is an idea we have borrowed from the Australian Constitution, which lists them as “concurrent powers” under Section 51 of its Constitution. Both the Commonwealth [equivalent to the Union government in India] and States can legislate on these subjects, although federal law prevails in the case of inconsistency. It’s the same case in India.

Besides this, we also borrowed ideas of freedom of trade between states and national legislative power to implement treaties, even on issues outside the jurisdiction of the Centre.

Liberty, Equality and Fraternity-France

The ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity, popularised by the French Revolution, laid the basis for the formulation of not just the fundamental rights, but the very freedom struggle itself. Even popular ideas of sovereignty and the republic, which India adopted, owes a lot to French political tradition.

Emergency powers-Germany

“The Emergency powers vested with President of India are on the pattern of similar powers conferred on the President of German Republic according to Article 48 of Weimer constitution of Germany. Nonetheless, these powers were later battered by Hitler when he came to power and assumed dictatorial authority,” says this note on Civil Services India.

India extensively borrowed from other Constitutions as well. From South Africa, for example, we have adopted a similar legislative procedure involved in passing constitutional amendments requiring 2/3 majority and electing members to the upper house based on proportional representation by the State legislatures. From Japan, meanwhile, we borrowed ideas on the procedure of making laws.

While our founding fathers borrowed ideas for the Constitution, the framing and execution of its provisions was driven by Indians to suit our realities. Take the example of secularism as articulated in this article. The Panchayati Raj system, meanwhile, is an Indian creation, which once again emerges from engagement with different constitutional systems.

Also Read: India’s ‘Conscience Keeper’: Why C Rajagopalachari & His Ideas Remain Relevant Today

“The Indian constitution used devices of liberal constitutional thought but rejected the liberal idea that constitutions had to perform the sole function of limiting state power. The Indian constitution had to empower the state to enter into the realm of Indian society and transform it by eradicating deeply embedded economic, political and social hierarchies. Whether the project of social transformation has succeeded or failed is another question. But the fact that the framers of the Indian Constitution attempted to use it as a means of revolutionising Indian society – which no country at that time had done – is something to be proud of,” says this blog written by the Centre for Law and Policy Research, a Bengaluru-based think-tank.

Beyond the framing of the Constitution, the Indian judiciary continues to accept “foreign constitutional doctrines and cases” while adjudicating domestic cases. It’s about keeping up with the times, and adopting best practices from other constitutional systems.

So yes, while we borrowed from various constitutions, “the credit [of crafting a constitution for India] goes to the Indians,” as Padma Shri-winning American expert on the Indian Constitution Granville Austin once said.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)